Archie here! In this historical study I discuss the topic of slavery and its fundamental causes. So many people today, especially in the Americas, are hyper sensitive to racial tensions, and many feel that racism was at the root of slavery. I make the case that racism was, not the cause of slavery, but one of its products. Also, we will discuss the case of slavery in the Americas as an example of two competing ways to interpret history; The materialist view and the Idealist view.

The Discovery of America

The fateful voyages of Christopher Columbus initiated an enormous exchange of goods and labor which lead mankind down the road of globalization. From 1492 onward, Europe’s experience with this new and strange world would be in many ways an experiment, with countless questions needing to be answered.

What would they do with this new discovery? At first it was gold and silver that attracted Europeans to the America, but soon the real gold-mine became a seemingly endless supply of land.

How would they make best use of this land? Such prime real-estate would prove vital in the expansion of Europe’s population and economy, producing crops, furs, lumber, and other goods. Yet this would also require a very large labor force.

Where would they find the man-power? The excess of booming European populations was utilized, as well as indentured servitude. But they also turned to a more archaic labor institution for this American experiment.

Slavery.

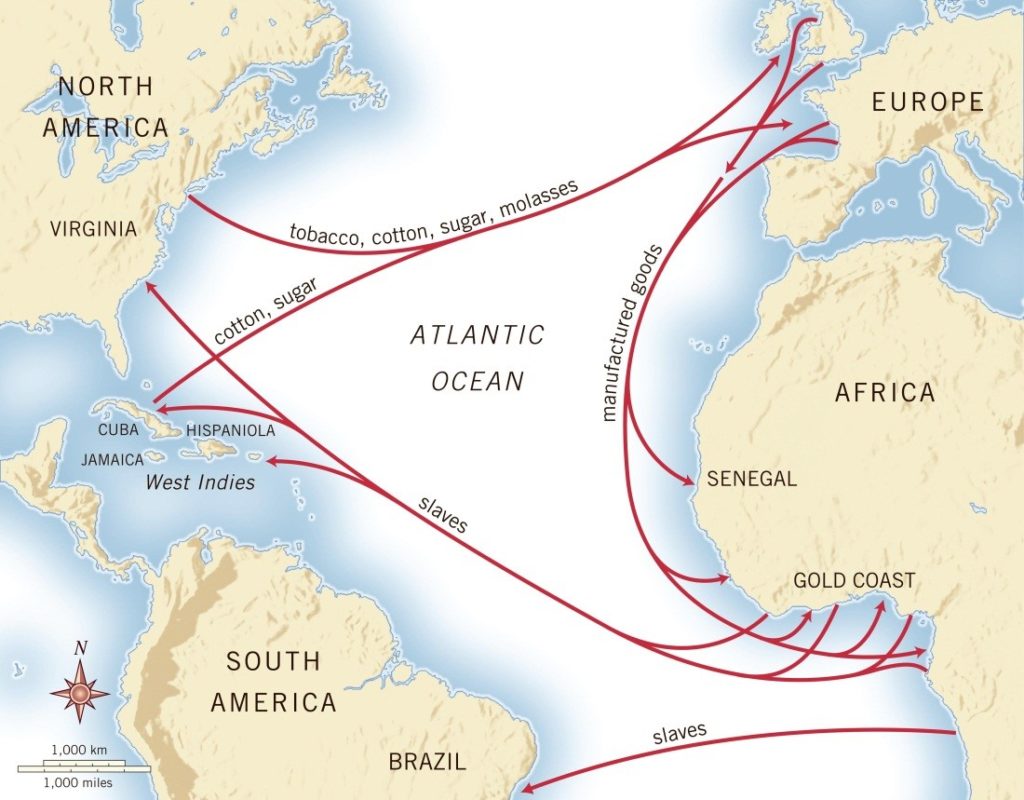

Thus the era of the “Middle Passage” was born, typically thought of as starting in 1502 when Spanish administrators first recorded the arrival of African slaves [1], and ending in the 19th century with the Emancipation Proclamation. For the western world, this time period saw the rise of powerful and dynamic empires, capitalism, religious reformations, and revolutions of both a political and social sort.

In a word, progress.

Yet through it all we find the relatively primitive institution of slavery driving much of the Colombian Exchange. Why did racialized African slavery start? More importantly, why did it gain such a profound cultural foothold? After all, the United States is still feeling the effects of slavery today long after the institution was abolished. In explaining the early history of European trans-Atlantic slavery, historians often take a comparative glance at ancient predecessors such as the Romans, who relied on their slave system to expand and develop. At the same time, however, this was very much a unique phenomenon in history. It was a slave system that was – more than any other – rooted in economics.

Some would advocate for more of an idealist approach, suggesting that attitudes and ideas played a role in its development. But overwhelming lines of evidence would dictate otherwise. The best approach when studying the early history of trans-Atlantic slavery is a materialist one, for three reasons;

(1) slavery itself is a legitimate economic system used in place of free-labor,

(2) it rose out of an economic need for cheap labor, and

(3) racial justification was really only a force in the later years of slavery as a result of its increasingly contradictory nature.

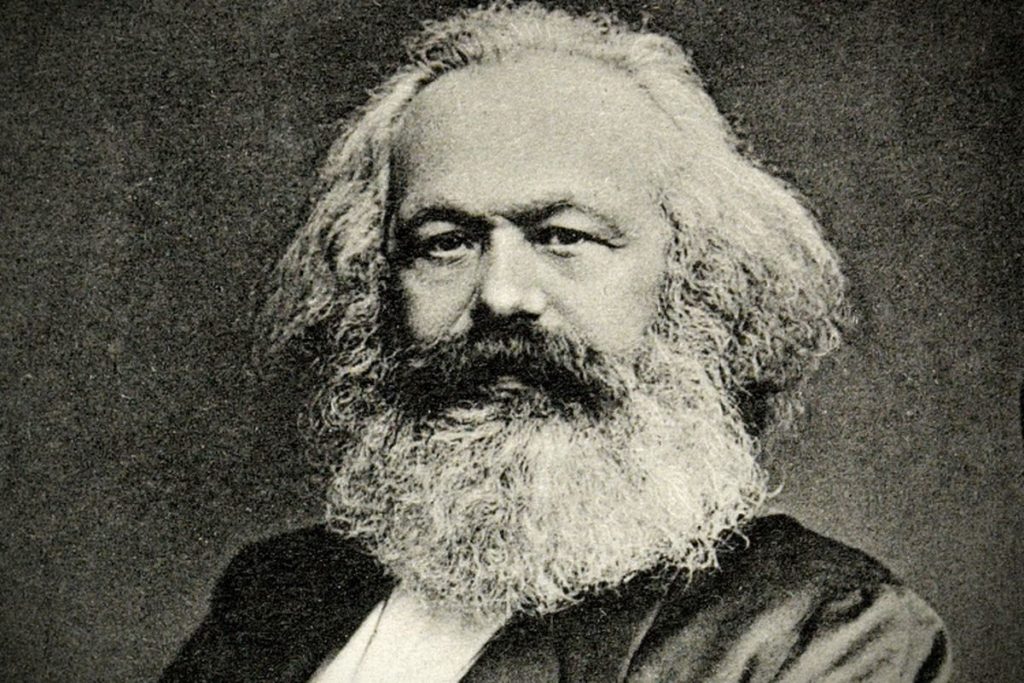

The Materialist Approach

What exactly is the materialist approach? The philosopher Karl Marx once proclaimed the “central dynamic” of history to be rooted in the “physiological and material needs” of mankind. History is, therefore, an on-going yet cyclical process based on “the way in which human needs are met.” This is the materialist view, one that carries much weight in explaining various events and phenomena throughout history. All humans have needs, and demand requires a supply. Raw materials and technology are important, but they must be combined with human labor in order to produce goods. In turn “the interaction between raw materials and human labour creates relations of production between people, and these relations may rest upon cooperation or subordination.” To a historical materialist, everything else in society (including our ideas and attitudes) derive from this need for production. Human society continues to evolve in order to more efficiently meet these needs, and the driving force for change is the class structure. [2]

While many would disagree with Marxist theory in some areas of the human experience, this view is consistent with the early historical development of slavery. Here we have a host of enterprising societies bent on making full use of new land. The raw capital was right there, waiting for human labor to cultivate it. The Europeans needed to use everything in their power to settle these lands, and slavery was a classic trick they had learned to use over the centuries.

The Romans utilized slavery during the heights of their empire. It was a substitute for the death penalty, commonly used on prisoners of war. [3] This was so ingrained into their society that in some areas of the empire three quarters of the population were enslaved. [4] Why didn’t the Romans just exterminate such people as perhaps the Nazi’s would have done in more recent experience?

It was mostly due to the fact that slavery was economically efficient for them. Even after the middle ages began and a feudal society with serf labor was created, slavery was still present in everyday life. Long predating the trans-Atlantic slave period in question, the Portuguese had been setting up trading posts along the West coast of Africa and importing slaves. [5] And hence when trade was being developed between the old and new world, slavery came automatically. As Edmund S. Morgan puts it, it was an “unthinking decision,” as settlers such as the British in Virginia “bought the cheapest labor they could get.” [6] So considering the history of slavery and how it was merely adapted to a new area, there really doesn’t seem to be any idealism involved. There was no big change in the thinking, slavery was simply a time-tested economic system that worked.

Other noted historians have come to understand that slavery is, at its heart, simply an economic system run by the “invisible hand” of capitalism as Adam Smith once put it. Robert Fogel described slavery as “one of the most long-lived forms of economic and social organization.” [7] Orlando Patterson further stated that “‘With slavery… the end is the profit of the master, his security, and public safety…’” and “In his powerlessness the slave became an extension of his master’s power.” [8] Eugene D. Genovese agrees with this idea, though he uses the term “instrumentum vocale,” or in other words the slave becomes “chattel, a possession, a thing, a mere extension of his master’s will.” [9]

Since slave labor was an economic institution with people being used as tools, and considering the clear system of subordination and cooperation to the end of production and profit, a materialist view would be much more applicable. It could be studied as labor history. Just like serfs, just like free-labor, it served the production needs at the time.However, there were key differences between slavery in the American colonies and slavery in ancient times. Up to that point slaves had only produced goods to be consumed by the family that owned them, or local markets. So they were more of an intimate part of society. Idealism may have played more of a role in such societies.

But trans-Atlantic slavery was completely different, almost serving as a primitive form of mass-production. About 80 percent of the goods produced on sugar plantations by slaves during this time went out to world markets. Another interesting fact is that between 1600 and 1800, slaves made up less than 1% of the world’s population, and yet the products of their labor dominated world trade. [10] These facts enhance in the minds of historians the importance of slave labor in the economic development of Europe at this time.

Indentured Servitude

Another factor that deserves attention is indentured servitude. Ira Berlin brings out the example of New England cereal farming during the colonial period. For most white farmers, “‘a Negro or black slave requires too much money at one time.’ And they relied instead on white indentured servants and free workers to supplement their own labor.” Simply put, it is less of an economic commitment to hire someone for a few years as opposed to life-long care and keeping.

Also, during times of disease and cold winters where black slaves died off by the score, slave-owners turned more toward indentured servants and free-labor. [11] On the other hand, during the middle of the 18th century as internal wars tore through Europe, there were less indentured servants being supplied. Since the demand for labor was only increasing during this period, more slaves had to be purchased. Some slaves were set free in the early years while some indentured servants were kept in service, and many African Americans were indeed free citizens. [12]

This seesaw motion of labor in the early to middle years of slavery illustrates the materialist idea that Europeans really just wanted labor in general, not slave labor in particular. Although the very fact that there were white indentured servants laboring alongside slaves in the first place virtually eliminates the theory that slavery rose out of the ideas and attitudes of Europeans such as racism and paternalism. It becomes quite clear that there was simply an economic need for cheap labor.

Another point on that note, something we see especially towards the beginning with slave labor is this notion of “sawbuck equality”. [13] The ideals of racism and white supremacy were really downplayed as soon as hard-times hit, especially in times where labor was scarce. Master and slave frequently had to work together in the field, literally “face-to-face on opposite sides of a sawbuck.” Whites depended on blacks to defend their homeland in times of invasion as well. Many African Americans joined the local militia, and were enlisted in the army. Does this come across as a product of idealism, or of economic need for labor? When it comes down to difficult times, such needs take a definite precedent over any quaint ideals men create.

The Beginnings of Racism

After slavery had been fully established in American society, ideas and attitudes started to develop. In this argument, it is significant to note that the idealism takes no major role in the early years of slavery. Genovese states in his work On Paternalism that “slavery as a system of class rule predated racism and racial subordination in world history and once existed without them.” [14] So while he emphasizes the ideals of paternalism, he admits that this was absent from the beginning of slavery. The concepts of white supremacy and racism were not as defined.

An example of this can be found in the exploits of Francis Drake, an English pirate who fought against the “tyrannical” Spanish government. When he arrived at Panama in 1572, he befriended a band of runaway black slaves. They joined forces against the Spanish, and the account gives no signs that there was any sort of mutual animosity based on race. They were just independent groups of people with the classic motto “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Applying this to early slavery, Africans were just a group of people who did work, fulfilling a need. Again, this was an institution that had existed for thousands of years in Africa, except this time they were selling themselves to the Europeans. Clearly it was a matter of class structure, not race. This was the case until slave codes were developed in the 1660’s. [15] After that, black slaves could not gain their freedom, whether they converted to Christianity or not.

Eventually the idea of black people being almost sub-human came into play, perhaps as a result of cognitive dissonance. There were many inconsistencies with slavery in a society that calls itself the “last best hope” for democracy and freedom. Indeed, the very values that America was founded on completely contradicted the institution that was central to their economy. But if they were to give up slavery, how could they fulfill their new economic needs? It was a far more simple solution to treat the slaves as lesser beings.

There came a point in the early 19th century where even this solution didn’t work, conveniently at a time when technology was beginning to supplement human labor. Abolitionists, for their part, started objecting to the institution of slavery on moral grounds. We see sentiment for this position through written documents such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stow and Frederick Douglas’ autobiography. There is certainly an element of idealism in the abolition of slavery, but this approach is less useful to a historian seeking to understand why African slavery was developed in the colonies of the new world.

Where Does the Evidence Lie?

Another reason why idealism is a less effective approach is the lack of evidence in terms of primary source documents. Since slavery was widely accepted as an age-old institution, the force of ideas didn’t get much attention, especially from the viewpoint of the slaves. Historians lament the difficulty of “recovering the past of a people who were relatively inarticulate, invisible, and illiterate.” [16] It requires innovative use of the sources we do have to establish a historical narrative, which only makes it easier for historians with preconceived notions to embellish facts. Meanwhile on the materialist side there are countless trade records and accounts, population censuses, and various other sources that help to establish the economic realities of slavery.

Further, perhaps the most powerful line of reasoning is that when we look at the history of slavery it doesn’t seem to be the force of ideas that dictated the institution, but rather once again economic need. How many slaves were imported in any given year? How many slaves were in Brazil versus Haiti? How were the slaves treated and what was the ratio of enslaved to free people in each area? The answers to all of these questions can be answered by reasoning based on economic supply and demand.

For example, European demand for sugar skyrocketed in the 16th century. As a result, between 60 and 70 percent of all Africans during this time were sent to Brazil, the world’s leading sugar producer. That would explain why Brazil had far more slaves than any other colony. [17] “Sawbuck equality”, referred to earlier, was practiced in areas where labor supply was down such as New England, and slaves were treated better in these areas. Thus the practical value of studying the economics of the development of slavery becomes clear. Idealism couldn’t play as big a role in our understanding, at least not regarding the early years.

Conclusion

To conclude, the introduction to “Slavery in American Society” brings out that “no one planned the creation of black slavery on the mainland of British North America. Like many other innovations in the New World, it was a synthesis produced by interaction between the colonists and their environment.” [18] This is consistent with Marx’s interpretation of history; that economic needs lead to an interaction between human society and its environment, which in turn leads to class relations and economic structures among humans themselves. Slavery is just one example of this.

Are there ideas and attitudes also involved in the history of American slavery? Indeed, but this aspect was not as important in the early development, and instead came about as a reaction to it later on. Ideas themselves find their source in human needs, as Marx would have it. As stated in The Houses of History, “He does not ascribe an independent existence to the realm of human consciousness and ideas, but perceives these as arising out of our material existence.” [19] While this may not hold true in some institutions, the case of trans-Atlantic slavery is clearly a materialist goldmine. If we continue to focus on the economics of slavery, studying trade records and other resources, our insight will continue to grow on the subject.

Works Cited

Goodheart, Lawrence B., Richard D. Brown, and Stephen Rabe, eds., Slavery in American Society, third edition. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Publishing, 1993.

Green, Anna and Kathleen Troup, eds.,

The Houses of History: A Critical Reader

in Twentieth-Century History and Theory. New York: New York University

Press, 1999.

[1] Goodheart, Lawrence B., Richard D. Brown, and Stephen Rabe, eds., Slavery in American Society, pg. xxiii.

[2] Green, Anna and Kathleen Troup, eds., The Houses of History pg. 34-36

[3] Slavery in American Society, pg. 3.

[4] Slavery in American Society, pg. 22

[5] Slavery in American Society, pg. xxiii

[6] Slavery in American Society, pg. 78

[7] Slavery in American Society, pg. 21

[8] Slavery in American Society, pg. 6,7

[9] Slavery in American Society, pg. 15

[10] Slavery in American Society, pg. 26,27

[11] Slavery in American Society, pg. 37, 43

[12] Slavery in American Society, pg. 63

[13] Slavery in American Society, pg. 46

[14] Slavery in American Society, pg. 14

[15] Slavery in American Society, pg. xxiii

[16] Slavery in American Society, pg. xxi

[17] Slavery in American Society, pg. 23-26

[18] Slavery in American Society, pg. xv

[19] The Houses of History pg. 34-36.

So What Do You Think?

Was modern day racism simply an invention to justify slavery? Why did it become so ingrained in American culture? Do you think History is driven by ideas, or economic need?